-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nicolae Radu Zabet, Boris Adryan, A comprehensive computational model of facilitated diffusion in prokaryotes, Bioinformatics, Volume 28, Issue 11, June 2012, Pages 1517–1524, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts178

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Motivation: Gene activity is mediated by site-specific transcription factors (TFs). Their binding to defined regions in the genome determines the rate at which their target genes are transcribed.

Results: We present a comprehensive computational model of the search process of TF for their genomic target site(s). The computational model considers: the DNA sequence, various TF species and the interaction of the individual molecules with the DNA or between themselves. We also demonstrate a systematic approach how to parametrize the system using available experimental data.

Contact: n.r.zabet@gen.cam.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Originally, it was believed that transcription factors (TFs) find their target sites only through 3D diffusion and the association rate would follow the Smoluchowski limit. Riggs et al. were the first to observe that the rate at which the lac repressor locates its target site is much faster than the rate predicted by the Smoluchowski limit and hypothesized that a different mechanism was involved in this process (Riggs et al., 1970).

In their seminal work, von Hippel et al. (Berg et al., 1981; Winter et al., 1981) thoroughly investigated this process from both a theoretical and experimental perspective and concluded that TF molecules use the facilitated diffusion mechanism to locate their target sites. This facilitated diffusion mechanism assumes a combination between 3D diffusion in the cytoplasm and an 1D random walk on the DNA. This leads to reduction of dimensionality in the search process and, consequently, speeds up the search. In addition, three main types of movements on the DNA were proposed: (i) sliding, (ii) hopping and (iii) jumping (Berg et al., 1981). Sliding and hopping are both mechanisms of 1D random walk, but the difference between them is that during hopping the molecules lose contact with the DNA, whereas during sliding the molecules keep contact with the DNA. On the other hand, jumping is a mechanism which assumes that the molecules do not only lose contact with the DNA for a short time interval (as in the case of hopping), but they completely release into the cytoplasm where they spend a longer time until they bind to the DNA uncorrelated with respect to the unbinding position.

The existence of the 1D random walk in vivo was recently confirmed by (Elf et al., 2007). The authors of that study used fluorescent lac repressor tetrameters and visualize their movement in a live Escherichia coli cell, confirming that the molecules spend 90% of the time bound to the DNA.

There are still missing pieces in our understanding of the facilitated diffusion mechanism. One approach to address these questions consists of building a computational tool able to simulate the relevant molecules in a cell and the entire DNA sequence. This type of approach can address several questions, e.g. how crowding can influence the search process at genome-wide level, in a dynamical context (Chu et al., 2009) and not as static barriers (Li et al., 2009). In addition, one could investigate systems with real affinity landscapes, which is not possible through analytical tools (Berg et al., 1981).

In this article, we present a computational model for stochastic simulation of the search process of TFs for their target sites on the DNA. The model considers each TF molecule as an independent object, which can move freely in the bacterial cytoplasm, but which also can bind to the DNA and perform an 1D random walk. The DNA molecule is modelled as a string of nucleotides, which leads to specific affinity between a TF molecule and DNA at the position where the molecule is bound. We also go through the literature and systematically infer each microscopic parameter of the model from experimentally macroscopic measurements.

Finally, we developed an implementation of the proposed model, which is available in Zabet and Adryan (2012).

2 MODEL

One strategy to stochastically model the TF search process for their target sites consists of designing a hybrid system combining agent-based modelling and stochastic simulation techniques (Gillespie, 1977). In this model, each TF molecule is represented as an agent able to perform certain actions and the DNA molecule as a string of the nucleotides: a, t, c or g. The model can assume reflecting boundaries (TFs that reach the boundary can only go back), periodic boundaries (the DNA is assumed to be in a closed loop) or absorbing boundaries (TFs that reach the boundary will unbind from the DNA).

In this setting, the TF molecules can be either free in the cytoplasm or bound on the DNA at a certain position. A free TF molecule has only one action available, namely, to bind to the DNA.

2.1 Binding event

We assume that the bacterial cytoplasm is a perfectly mixed reservoir from where the free TF molecules bind to the DNA. The 3D diffusion of TF molecules in the cytoplasm is not modelled explicitly, but rather, the molecules that are free in the cytoplasm have a certain association rate to the DNA. To simulate 3D diffusion we use the Direct Method implementation of Gillespie Algorithm (Gillespie, 1977) which generates a statistically correct trajectory of the Master Equation.

Note, that after each 1D move, the number of available positions on the DNA for a TF to bind can change and, consequently, the association rate needs to be updated often. An approximate system would consider that the binding of TF molecules is affected by occupancy, but the update is performed only when a molecule binds/unbinds and not when any other event (sliding or hopping) would lead to change in the number of available binding sites on the DNA. In the Supplementary Material, we show that the difference between this approximation and the exact system is negligible and, thus, one can use this approximate system to increase simulation speed.

TF binding to the DNA. TF molecules bind to the DNA and mark several nucleotides as covered (grey) on: the DNA binding motif (3 bp in our example), the obstructed left side (1 bp) and the obstructed right side (2 bp). Volume exclusion is implemented, in the sense that two TF molecules cannot cover the same base pair on the DNA. The green positions on the DNA mark the positions where the free TF molecule can bind.

We mark all base pairs covered by the TF molecule as being unavailable, but we record the left-most base pair covered by the TF molecule as the position at which a TF molecule is bound to the DNA. This does not affect the results in any way, but is just a choice of internal representation of the binding.

In addition, previous simulators did not take into account TF orientation on the DNA (Barnes and Chu, 2010; Chu et al., 2009). The orientation of TFs affects the affinity of the TF for a specific position on the DNA, i.e. a molecule bound in one orientation can have a totally different affinity compared with being bound in the opposite orientation at the same position.

Finally, since transcription and translation are co-localized in prokaryotic systems, a TF molecule has a higher probability to bind initially near the DNA region where it was released, and if the target site is within a sliding length distance, the entire search process can be reduced to one sliding step. We consider the possibility of an initial binding region on the DNA in our model, in the sense that each TF molecule has a user-specified probability to bind for the first time within the user-defined region on the DNA, but only if there are free spots in that region.

2.1.1 Implementation of the binding event

Barnes and Chu (2010) observed that, in the case of crowded DNA, locating a free position on the DNA where TF molecules can bind can be a bottleneck. In the Supplementary Material, we present a new method to significantly enhance the simulation speed. This method assumes the creation and maintenance of an array list of boolean values for each TF species (x), which specifies whether a TF molecule of type x is allowed to bind at position j, A[x][j]. This has the purpose to eliminate the need to check if sufficient nucleotides (TFsizex) in the right side of the selected position are not covered by other molecules.

Furthermore, to increase the speed of locating a position, we store the current number of free positions for each species, Axcurrent, and when we look for a free position we draw a random number z in the interval [0, Axcurrent) which will represent the z-th available position on the DNA. This method guarantees that a free position is found using only one random number, which represents a significant enhancement of the simulation speed. To further increase the search speed from M/2 to  , we keep total counts of available positions in a different array (see Supplementary Material).

, we keep total counts of available positions in a different array (see Supplementary Material).

2.2 TF affinity for DNA

To reduce memory usage, we will break the TF species into two classes: (i) non-cognate TFs and (ii) cognate TFs. The cognate ones are the TFs that are of interest and that we can follow, whereas the non-cognate ones main purpose is to simulate the ‘other’ proteins on the DNA, which might interfere with the search process of the cognate TFs. For efficiency reasons, we pre-calculate the affinities of each TF species, both cognate and non-cognate, and store them in individual arrays. The non-cognate binding energy is randomly generated using a Gaussian distribution with the mean and variance provided as inputs for each non-cognate species.

The binding energy of cognate TFs is computed using two techniques: (i) mismatch energy (Gerland et al., 2002) and (ii) position frequency matrix (PFM; Berg and von Hippel, 1987; Stormo, 2000). In both scenarios, we assume that each position in the DNA binding motif is approximately independent and additive (Berg and von Hippel, 1987; Gerland et al., 2002; Stormo, 2000).

Note that the binding energies computed by the three methods for the lac repressor and the E.coli K-12 genome are highly correlated and they follow a Gaussian distribution (see Supplementary Material).

2.3 One-dimensional random walk

The TF molecule will reside at its current position on the DNA for a random amount of time, which is exponentially distributed with a mean τxj. Once a TF molecule was selected to perform an action from its current position on the DNA, the molecule has to chose stochastically between one of the following three actions: (i) unbind from the DNA (with the possibility to re-bind fast), (ii) slide left on the DNA and (iii) slide right on the DNA. The probability to perform any of these actions (Punbind, Pleft and Pright) is independent of position, but it is specific to each TF species, i.e. each TF species has its own values for the probabilities to perform these actions (Punbindx, Pleftx and Prightx for species x) and a molecule of type x has the same probabilities independent of the position on the DNA (Punbindx[j]=Punbindx, Pleftx[j]=Pleftx and Prightx[j]=Prightx, ∀j, where j is the position on the DNA). Note that, to make the notation simple, we will drop the superscript x from the these parameters, but, whenever we refer to these action probabilities, it is understood implicitly that they are specific to each TF species. Furthermore, in this article, we assume an unbiased random walk (for a discussion on this aspect see Section 5) and this means that the probabilities to slide left or right are equal at any position on the DNA, Pleft[j]=Pright[j], ∀j (where j is the position on the DNA).

First, if the molecule ‘decides’ to unbind, it will have a high probability to re-bind fast (van Zon et al., 2006). Theoretical studies computed that a TF re-binds on average between six times (Wunderlich and Mirny, 2008) and up to a few hundred times (DeSantis et al., 2011). The model allows for each species to have two unbinding probabilities: (i) the unbinding probability (with the possibility to re-bind fast) (Punbind) and (ii) the probability to completely release from the DNA once unbound (Pjump). The former controls the number of sliding steps the TF performs before it unbinds, whereas the latter controls the ratio between the number of hops and the number of complete dissociations from the DNA.

We should mention that we do not distinguish explicitly between jumps and long hops. In particular, a disassociated molecule can re-bind to a position which is Gaussian distributed around its previous position and with variance σ2hop=1 bp (Wunderlich and Mirny, 2008). Thus, long hops are allowed as long as the re-binding is fast. In addition, if the TF molecules have orientation, then during hopping, the orientation of a TF can change. For slow re-binding the TF molecules are released into the cytoplasm and they will have chances to re-bind similar to all free molecules.

2.3.1 Implementation of the 1D random walk

There are two strategies to implement the 1D random walk (see Supplementary Material). First, we can consider all molecules as independent agents that stay at their current position for a certain amount of time. Then, we store the time when each molecule will attempt to make a new action in a sorted structure (such as PriorityQueue in Java). This list is kept updated and sorted after each 1D or 3D random walk event. When selecting the next event to execute, we pop the head of this structure. We call this method the First Reaction (FR) method.

Second, we keep the waiting times in a fixed size array and extract the next molecule that is bound to the DNA and that will perform an action. This is based on the Direct Method version of the Gillespie algorithm (Gillespie, 1977) and, thus, we call this the Direct Method.

2.4 Cooperativity

The cooperativity can be reversible, in the sense that once the TF molecule of species x located at site j moves away, the waiting time of a molecule of type y at the position j′ reverts to the original value, τyj′. Nevertheless, the cooperativity can be irreversible, and the waiting time of a molecule of type y at the position j′ can be kept at the value  until molecule y leaves position j′.

until molecule y leaves position j′.

Equations (8) and (9) were already discussed in Chu et al. (2009). In addition, Equations (10) and (11) represent new hypotheses of how to model cooperativity that are mathematically possible and which we would like to further investigate for their biological relevance. In the case of Equation (9), we assumed that the residence time will increase with a fix value independent of where two TF molecules are on the DNA. Although this might represent a good approximation, there is no clear evidence that the increase in affinity is not dependent on the strength of the binding between TFs and DNA. Equation (11) provides a way to model direct TF–TF co-operativity which depends on the strength of the TF-DNA binding. This type of interaction has not been investigated previously, but the framework that we present here aims to propose several new hypothesis that could be further tested.

3 ESTIMATING MODEL PARAMETERS

The model requires a series of microscopic parameters. Next, we will systematically show how to estimate these parameters in our system from macroscopic parameters that were measured experimentally. We consider the lac repressor and E.coli as an example system, due to the fact that it is a well-studied system with some available data. Note that unless mentioned otherwise, we will use the genome of E.coli K-12, which has M≈4.6 Mbp (Riley et al., 2006).

First, if we know that the observed sliding length is slobs and that the random walk is unbiased, then during a sliding event we will need Nseobs=(slobs)2/2 sliding events to cover slobs base pairs of DNA (Wunderlich and Mirny, 2008).

If we consider that TFs spent 90% of the time bound to the DNA (f≈0.9 relative time bound to the DNA Elf et al., 2007), then, at any time point, on average 90% of the molecules will be bound to the DNA (TFbound/TFfree=9). In this scenario, the association rate is somewhere in the interval kassocx∈[2000, 3600]s−1.

Finally, knowing the average number of non-cognate molecules (TFnc ~ 104), the DNA occupancy (TFnc·fnc·TFncsize/M∈[0.1, 0.5]) and the length of the (DNA M=4.6 Mbp), we can estimate that the average number of base pairs covered by a non-cognate molecule is TFsizenc=46 bp. For 10 000 non-cognate molecules (each covering 46 bp) 460 000 bp of the DNA will be covered by non-cognate molecules, which represents 10% of the entire DNA. In the other extreme, for 50 000 molecules, 2 300 000 bp of the DNA will be covered by non-cognate molecules, which represents 50% of the entire DNA. Similarly, one could use TFsizenc=23 bp and the non-cognate abundance in the interval [20000, 100000].

4 VALIDATING THE MODEL

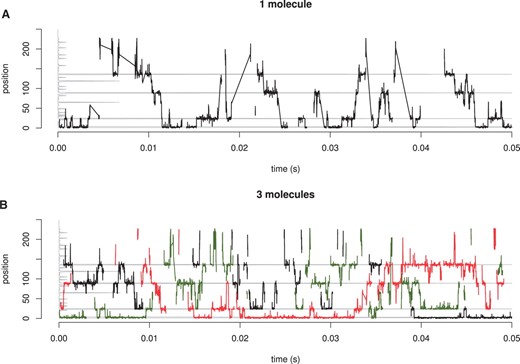

Next, we will show some simple tests we conducted to visualize the behaviour of the system, under different conditions. First, we want to demonstrate how the molecules move on the DNA during a simulation run. Figure 2 shows an example of a random walk performed by 1 or 3 molecules on a 250 bp randomly generated DNA sequence. The molecules alternate the 1D movements (high-density regions in Fig. 2) with 3D excursions or hops (low-density regions in Fig. 2).

Dynamic behaviour of TF molecules. We consider a random 250 bp DNA and TF molecules which can bind/unbind, hop, jump, slide left/right. (A) 1 TF molecule (B) 3 TF molecules. The position of the molecules is represented on y-axis and the time on the x-axis. The grey line on the y-axis represents the affinity at that position for a TF. Note that after a complete dissociation of a TF from the DNA the line that follows the position is broken as opposed to a line connecting two dense regions which describes a hop or a correlated jump.

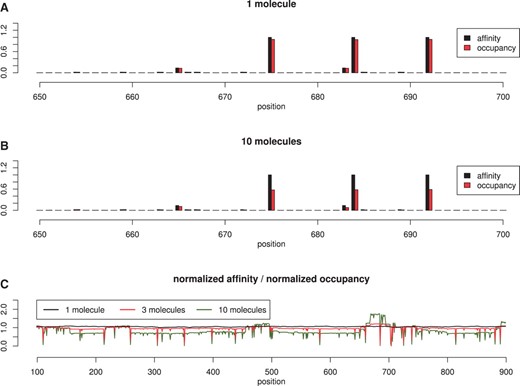

One simple test consists of plotting the normalized affinity versus the normalized occupancy for each position on the DNA after the simulator is run for a long-time interval. The top graph in Figure 3 shows that there is a strong positive correlation between occupancy-bias on the DNA and affinity, in the case of 1 TF molecule in the system.

Affinity vs occupancy. We consider a random 1000 bp DNA strand and TF molecules which can bind/unbind, hop, jump, slide left/right. In (A) we show the normalized affinity and normalized occupancy for 1 molecule and in (B) for 10 molecules. In (C) we plot the ratio between occupancy and affinity, which should be ~1 for highly correlated values. The Pearson, coefficient of correlation between the the affinity and occupancy slightly drops from 0.999 (in the case of 1 molecule) to 0.998 (in the case of 3 molecules) and, further, to 0.979 (in the case of 10 molecules).

Furthermore, in the case of multiple molecules of the same TF species, the affinity and occupancy have a strong correlation, but not as good as in the case of 1 molecule (see middle plot of Fig. 3). This suggests that in the case of crowding and competition for DNA space, the affinity between TF molecules and DNA is not the sole determinant of the occupancy-bias. Inverting this statement, we could say that occupancy-bias is not necessarily equivalent to the affinity landscape, in the sense that regions that are occupied most of the time are not necessarily the highest affinity ones. However, this was observed at 1 bp resolution and it might be averaged out on larger sectors of DNA.

Finally, we would like to mention that in the Supplementary Material, we systematically investigated the quality of our approach to estimate model parameters. The results showed that setting the model parameters using our approach leads to negligible errors between the desired system behaviour and the measured one in the simulations.

5 CONSIDERATIONS ON THE MODEL

One question that one might ask is whether our coarse-grained model of 3D diffusion will capture all the details of a real 3D particle simulator. van Zon et al. (2006) observed that the zero-dimensional Chemical Master Equation can accurately model the association rate between TF molecules and the DNA, as long as the model considers fast re-binding in close proximity after an unbinding event. Since we implemented fast re-binding in our model (through hops), we conclude that the 3D diffusion model employed in this contribution reliably represents the 3D diffusion of TFs in the cytoplasm.

Furthermore, we did not consider the 3D shape of the DNA in our model. Nevertheless, the shape of the DNA is likely to affect only two variables in the model, namely: (i) the average number of re-bindings [because it is expected that once trapped in dense DNA areas, the TF molecules will find it more difficult to escape the DNA (Bancaud et al., 2009)] and (ii) the areas of the DNA where a TF will hop [hopping is more likely to lead to small 1D displacement, but in the case of close 3D proximity, this might result in more jumping (Lomholt et al., 2009)]. Both of these parameters are fine-tunable within our model, so by increasing the hopping lengths and the number of fast re-bindings, 3D effects could be integrated in the model.

In addition, we also make the assumption that the 1D random walk is unbiased. However, some previous models of sliding considered that the 1D random walk is biased, in the sense that depending on the left or right side affinities from the current position a TF molecule might have different probabilities to slide in one or the other direction (Slutsky and Mirny, 2004). This was supported by the fact that the affinity landscape of RNAp seems to increase when moving towards the transcription start site (TSS) and consequently the RNAp can be directed towards the TSS (Weindl et al., 2007).

Barbi et al. (2004) showed that in the case of bias, the random walk displays initially a sub-diffusive behaviour which can last significantly long. However, Blainey et al. (2006) did not observe any anomalous 1D diffusion when a hOgg1 protein would perform a random walk on the DNA in vitro, but rather concluded that the random walk is unbiased. Since there is no strong experimental evidence for the fact that biased random walk is a general mechanism in the search process, we considered in this contribution that the random walk is unbiased.

Finally, in comparison to a different implementation strategy, the memory model proposed by (Barnes and Chu, 2010), our implementation strategy showed an increase in speed (see Supplementary Material). The disadvantage of our strategy is that creating an array with the same size as the DNA for each TF species, will result in larger memory requirements compared with the memory model of (Barnes and Chu, 2010). For the entire genome of E.coli (4.6 Mbp) and two TF species, a non-cognate and a cognate one, the simulator will require approximately 2 GB of RAM. Although the simulator permits to specify input several species of TF, extra care should be taken when adding new species into the simulator due to the extra memory usage. Each new TF species added to this system (E.coli) will increase the required memory by a few hundred MB (≈300 MB) for a DNA sequence of 4.6 Mbp. However, we consider our strategy as a good compromise in cases were simulation speed is essential.

6 DISCUSSION

Previously, facilitated diffusion was modelled mainly analytically (e.g. Berg et al., 1981; Mirny et al., 2009). Although these types of models brought new insights into the mechanism, they mainly lack the capability to integrate real DNA sequence (a non-uiniform TF affinity ‘landscape’; Mirny et al., 2009) and/or dynamic crowding (mobile ‘roadblocks’; Flyvbjerg et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009). Nevertheless, computational models are able to surpass these shortcomings.

Stochastic simulations have revolutionized the way theoretical biologists can nowadays deal with problems that are not easily amenable to experimental measurements. TF target finding belongs to a class of spatio-temporal problems that, in a first approximation, may be addressed with tools that simulate 3D diffusion, e.g. Smoldyn (Andrews et al., 2010). However, due to the particular behaviour of DNA-binding proteins and the proposed facilitated diffusion mechanism, the Smoluchowski limit is overcome. For a meaningful outcome from any simulation experiment, a more detailed model is therefore required. In order to produce results in a relatively short time, previous computational models of facilitated diffusion were limited by size of the analyzed system or level of details included in the model. For example, the work of (Das and Kolomeisky, 2010) and (Wunderlich and Mirny, 2008) did not consider specific affinities between TF and DNA, while more detailed models as the one presented by (Chu et al., 2009) could consider at most 40 kbp per DNA strand.

Our model includes new features that were not previously considered in this type of modelling, such as TF orientation on the DNA and the fact that TF can cover more base pairs than the actual DNA binding domain. In addition, we also suggested an implementation strategy that allows for genome-size DNA sequences to be simulated, a clear advantage over previous tools there were limited to few thousands base pairs (Chu et al., 2009).

Not only does our work proposes a detailed model of the facilitated diffusion mechanism with a highly efficient implementation strategy, but also presents a systematic and comprehensive assessment of crucial parameters in this system. As an example, we use (Elf et al., 2007) measurements of the lac repressor system in E.coli. In particular, we show that using our comprehensive parameter estimation, our model displays similar behaviour as in (Elf et al., 2007), i.e. residence time of tR=5 ms, actual sliding lengths of slobs=90 bp, the relative time the molecules stays bound to the DNA of f=0.9 and the 1D diffusion coefficient of 0.046 μm2s−1.

It can therefore be concluded that for future studies on TF target finding in prokaryotic systems, our model represents an ideal entry point for stochastic simulations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Robert Foy and Robert Stojnic for useful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Funding: Medical Research Council [G1002110 to N.R.Z.] and Royal Society [to B.A.].

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Associate Editor: John Quackenbush