-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Karin Verspoor, Daniel Dvorkin, K. Bretonnel Cohen, Lawrence Hunter, Ontology quality assurance through analysis of term transformations, Bioinformatics, Volume 25, Issue 12, June 2009, Pages i77–i84, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp195

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Motivation: It is important for the quality of biological ontologies that similar concepts be expressed consistently, or univocally. Univocality is relevant for the usability of the ontology for humans, as well as for computational tools that rely on regularity in the structure of terms. However, in practice terms are not always expressed consistently, and we must develop methods for identifying terms that are not univocal so that they can be corrected.

Results: We developed an automated transformation-based clustering methodology for detecting terms that use different linguistic conventions for expressing similar semantics. These term sets represent occurrences of univocality violations. Our method was able to identify 67 examples of univocality violations in the Gene Ontology.

Availability: The identified univocality violations are available upon request. We are preparing a release of an open source version of the software to be available at http://bionlp.sourceforge.net.

Contact: karin.verspoor@ucdenver.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

It has been previously noted that terms in structured controlled vocabularies, such as the Gene Ontology (GO) (The Gene Ontology Consortium, 2000), often have a highly regular, even compositional, linguistic structure and that this structure can be exploited for the purposes of accessing those terms computationally and reasoning over them (Mungall, 2004; Ogren et al., 2004; Verspoor, 2005). This regularity is particularly important now that there are efforts to perform intra- or inter-ontology enrichment by linking terms (Bada and Hunter, 2008), because the tools that are used to support these efforts analyze the formal structure of the terms and take advantage of patterns of expression. The more consistency in expression there is, the more terms will be able to be appropriately and automatically linked. It is also intuitively important for human usability of the ontologies—the more consistently concepts are phrased, the easier the resource should be to search and augment.

We call the consistency of expression of concepts in an ontology univocality, inspired by the philosophical term referring to a shared interpretation of the nature of reality (Spinoza, 1677). In this article, we take univocality to be a primary goal for assuring ontology quality.

Community efforts in the development of ontologies and lexical resources generally involve contributions from across various research or database groups. Given that different individuals are contributing new terms and changes to existing terms in ontological resources, it is possible that there will be terms that do not follow established conventions for the expression of concepts. It is important for maintenance of the quality of the ontology to identify such terms and correct them to be univocal, or consistent with similar terms. This has, in fact, been identified as a major concern for ontology quality by the curators of the GO (Hill, personal communication, January 11, 2008).

One of the concerns the GO curators raised is the potential occurrence of redundant terms in the ontology—terms expressing the same meaning with two distinct forms (e.g. ‘regulation of transcription’ and ‘transcription regulation’). This is the most basic case of a univocality violation, and would certainly indicate an error in the ontology. However, in our work on the GO we were not able to identify any such cases. Rather the univocality failures occurred in semantically similar, rather than identical, concepts expressed using different forms. We thus generalize the notion of univocality in this work to apply to similar concepts and thereby assess the ontology quality more broadly.

A common theme of research on ontology quality assurance is that even manually curated lexical resources contain some percentage of errors. Even heavily curated ontologies with strict guidelines can suffer from consistency problems, perhaps due to their size and the number of people involved in their development. Smith and Ceusters have worked on two aspects of quality assurance for ontologies: in Kohler et al. (2006) they presented a technique for automatically locating circular or difficult-to-read definitions in the Gene Ontology, and used it to identify 6001 potentially deficient definitions in this resource. Ceusters et al. (2004) proposed three algorithms for detecting errors in biomedical ontologies, and applied them to SNOMED-CT. They uncovered a small number of faulty relations between concepts, and a large number of redundant concepts. Cimino has worked on quality assurance for relations in the Unified Medical Language System. Cimino et al. (2003) used mismatches between the semantic types of parent and child nodes linked via the IS-A relation to uncover inconsistencies in the UMLS Metathesaurus. They found that 59% of a small manually examined sample of the over 17K relations uncovered by their technique were incorrect. They also detected some pairs of concepts that should have been linked via IS-A, but were not. Cimino (1998, 2001) applied an automated methodology for detecting ambiguity and redundancy in the UMLS Metathesaurus to two revisions of that lexical resource and found that his methods continued to find errors in the Metathesaurus even after 6 years of manual curation. In fact, even studies not specifically targeting error detection in ontologies have uncovered significant faults in them as a side effect of other work. For example, Ogren et al. (2004) used a standard discovery procedure from descriptive linguistics, normally used to study morphology, to investigate the formation of terms in the GO. As an incidental finding, they discovered many sets of terms—for example, ‘cell proliferation’ and ‘regulation of cell proliferation’ —that intuitively should have been linked in the ontology, but were not. This finding led the GO Consortium to add a large number of links in a subsequent revision of the ontology.

We introduce an automated methodology for identifying potential failures of term univocality and apply the method to the GO to discover a small but significant number of terms that should be rephrased to improve the overall quality of the ontology.

2 APPROACH

Our goal is to detect sets of terms within a controlled vocabulary that express similar concepts using different surface forms and are therefore not univocal. We approach this problem through term transformation and clustering. We hypothesize that pairs of terms which are not univocal will be transformational variants of one another, such that when they are normalized to a common representational form they will cluster together. We automatically apply transformations to the terms in the vocabulary in order to normalize their form and group terms that have the same form as a result of these transformations together into a cluster. We then utilize an automated heuristic search over the term clusters to identify term occurrences that are expressed non-uniformly, as compared with similar terms. This basic strategy of transforming and clustering was successfully applied to LocusLink by Cohen et al. (2002) to uncover erroneous names/symbols in that resource, though their approach targeted character-based and syntactic units, while our approach emphasizes semantic units.

A pair of terms which are not univocal in the GO appears in Example 1. For consistency, one of these terms should be rephrased, e.g. GO:0009558 could be rephrased ‘embryo sac cellularization’ in order to align not only with the other term shown here, but also GO:0009553, ‘embryo sac development’ and similar terms.

Example 1.

GO:0009558 – cellularization of theembryo sac

GO:0009562 – embryo sacnuclear migration

Ogren et al. (2004) showed that a large proportion (65.3% in their study) of GO terms contain another GO term as a proper substring. Here, we draw on that insight and perform substitution of the embedded GO term with a generic label in order to better capture the overall structure of the (larger) term. We similarly search for embedded occurrences of terms from the Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI) ontology (Degtyarenko, 2003) and substitute them with a distinct generic label.

The three transformations we perform are as follows:

Abstraction: identification of GO or ChEBI terms embedded in a longer GO term, and replacement of this embedded term with a generic GTERM token, for an embedded GO term, or CTERM token, for an embedded ChEBI term.

Stopword removal: elimination of stopwords, or words which do not normally carry semantic content, such as the, of, etc.

Reordering: alphabetic ordering of the tokens within the term.

Each cluster is identified with a three-digit binary code indicating the transformations applied (xyz, where x = 1 when abstraction is performed, y = 1 when stopword removal is performed and z = 1 when the tokens are alphabetically ordered) plus the resulting generalized form of all of the terms in the cluster. So, for instance, all of the terms in Example 2 correspond to the cluster 111 {CTERM CTERM oxidati}, indicating that after all three transformations have been applied, those terms collapse to that form, consisting of two ChEBI terms and the stem oxidati (see Section 3 for a discussion of the approach to stemming we used).

Example 2.

111 {CTERM CTERM oxidati}

GO:0019327 – oxidation of lead sulfide

GO:0018158 – protein amino acid oxidation

GO:0019604 – toluene oxidation to catechol

GO:0019602 – toluene oxidation via 3-hydroxytoluene

GO:0019603 – toluene oxidation via 4-hydroxytoluene

GO:0019601 – toluene oxidation via 2-hydroxytoluene

GO:0019479 – L-alanine oxidation to propanoate

GO:0019696 – toluene oxidation via toluene-cis-1,2-dihydrodiol

After the transformation and clustering steps, we apply a heuristic search1 over the generated clusters to identify potential univocality violations. This is an automated search over the full set of clusters (for all xyz combinations) that draws on the intuition that the abstraction transformation is fundamental to identifying univocality violations—without it we are limited to only considering terms that are near identical at the string level—and that this transformation is the necessary starting point for our univocality analysis. Thus, we only consider clusters for which abstraction has been applied (1yz clusters, i.e. 100, 101, 110 and 111 clusters) in our search. The algorithm specifically looks for terms which appear in distinct clusters at the 100 level of generalization, but merge together upon application of one of the other transformations. This cluster merging indicates that the terms in the 100 clusters are semantically similar, but that they differ in terms of either their word order or the stopwords they contain. These differences may indicate a univocality failure. The clusters identified automatically in this way are then examined manually for terms which appear to violate univocality, such as GO:0019327 above, which should be phrased ‘lead sulfide oxidation’ for consistency, and categorized as either a true positive cluster (containing a univocality violation) or a false positive cluster (not containing a univocality violation).

3 METHODS

We worked with a December 2007 download of the GO, and release 48 of ChEBI. As a result of the older GO version we used, some true positive results reported here now correspond to obsolete terms. We are preparing a release of an open source version of the software that will be made available at http://bionlp.sourceforge.net.

All words in all terms are preprocessed according to the following steps. First, all letters are converted to lower case and punctuation such as hyphens and commas are removed. Then words are stemmed by truncating all words longer than seven characters to a length of seven, e.g. ‘reproduction’ and ‘reproductive’ are both stemmed to ‘reprodu’. This simple approach was found to be more useful for biological terms than other commonly used stemming methods such as the Porter (1980) stemmer. The truncation length was chosen empirically.

After preprocessing, all combinations of the transformations are performed to generate clusters of the terms according to the approach described above. The abstraction step, when performed for the 1yz transformations, is always done prior to the other two transformations to avoid spurious matches of a substring to a superficially similar GO or ChEBI term. It requires an exact match of a substring to a full term in the relevant vocabulary. Terms are tested for matches in descending order of length, so the longest possible matching term is always replaced with the appropriate CTERM or GTERM token. The stopword list we use is the list from PubMed, with the addition of the single digits 0–9 and the word ‘an’.

For this study, we maintain redundancy in the cluster representations such that for instance the term GO:0019480—l-alanine oxidation to pyruvate via d-alanine—does not cluster with the terms in Example 2 after transformation but rather by itself in 111 {CTERM CTERM CTERM oxidati} due to the occurrence of three ChEBI terms, rather than two, within that GO term. This was done after initial analysis showed that elimination of redundancy removed too much term expression variation and resulted in a high number of false positives for the univocality violation detection.

When applying our heuristic search, we discovered that some clusters contained only terms that had slight naming variations and did not in fact indicate a true univocality violation. The script was updated to filter such clusters out and the results reported here include that filtering. An example of the sort of cluster removed from the set of potential univocality violations with this filter is shown in Example 3.

Example 3.

110 {proprot convert activit}

GO:0004285 – proprotein convertase 1 activity

GO:0004286 – proprotein convertase 2 activity

GO:0016808 – proprotein convertase activity

4 RESULTS

Table 1 shows the number of clusters generated for each transformation combination from 25 539 source GO terms processed, indicating the amount of generalization introduced by each transformation. We see from row 000 that the preprocessing step already collapses terms together (with about a 8% reduction in the number of clusters from the starting point where each term is assigned a unique cluster) due to singular/plural variation and words that have a common stem. For instance, all terms such as ‘interleukin-1 binding’, ‘interleukin-25 binding’, etc., cluster together as 000 {interle binding}. We also see that even after applying all transformations, many terms do not cluster with other terms. This is generally because the terms contain a specific named entity neither in ChEBI nor in the GO itself, for instance ‘eosinophil chemotaxis’ or ‘1,4-lactonase activity’, or are simply structurally unique in the GO, e.g. ‘embryo implantation’.

Number, mean and maximum (max) size of clusters for each xyz transformation combination

| xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . | xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000 | 23 478 | 1.088 | 29 | 100 | 12 704 | 2.010 | 2999 |

| 001 | 23 395 | 1.092 | 29 | 101 | 12 594 | 2.028 | 3003 |

| 010 | 23 400 | 1.091 | 31 | 110 | 12 564 | 2.033 | 3012 |

| 011 | 23 294 | 1.096 | 31 | 111 | 12 354 | 2.067 | 3054 |

| xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . | xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000 | 23 478 | 1.088 | 29 | 100 | 12 704 | 2.010 | 2999 |

| 001 | 23 395 | 1.092 | 29 | 101 | 12 594 | 2.028 | 3003 |

| 010 | 23 400 | 1.091 | 31 | 110 | 12 564 | 2.033 | 3012 |

| 011 | 23 294 | 1.096 | 31 | 111 | 12 354 | 2.067 | 3054 |

x is abstraction, y is stopword removal and z is token reordering.

Number, mean and maximum (max) size of clusters for each xyz transformation combination

| xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . | xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000 | 23 478 | 1.088 | 29 | 100 | 12 704 | 2.010 | 2999 |

| 001 | 23 395 | 1.092 | 29 | 101 | 12 594 | 2.028 | 3003 |

| 010 | 23 400 | 1.091 | 31 | 110 | 12 564 | 2.033 | 3012 |

| 011 | 23 294 | 1.096 | 31 | 111 | 12 354 | 2.067 | 3054 |

| xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . | xyz . | Count . | Mean . | Max . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000 | 23 478 | 1.088 | 29 | 100 | 12 704 | 2.010 | 2999 |

| 001 | 23 395 | 1.092 | 29 | 101 | 12 594 | 2.028 | 3003 |

| 010 | 23 400 | 1.091 | 31 | 110 | 12 564 | 2.033 | 3012 |

| 011 | 23 294 | 1.096 | 31 | 111 | 12 354 | 2.067 | 3054 |

x is abstraction, y is stopword removal and z is token reordering.

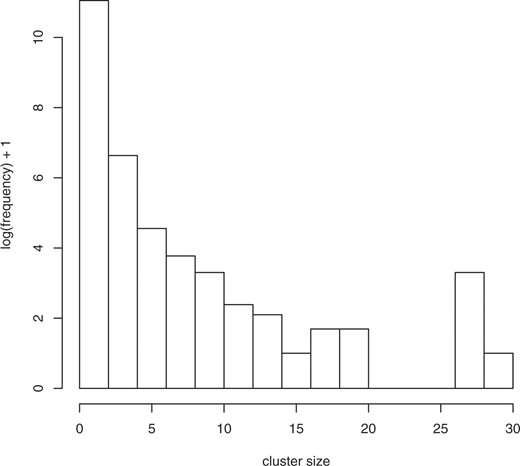

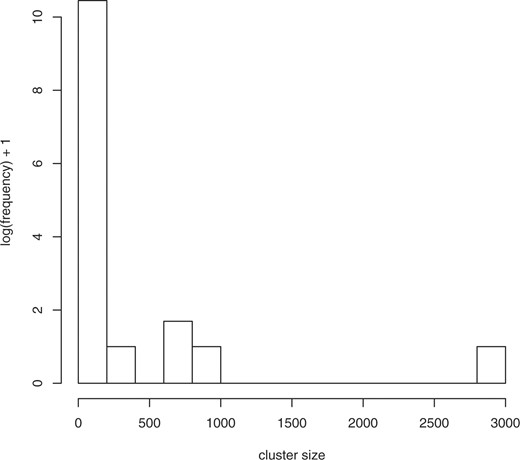

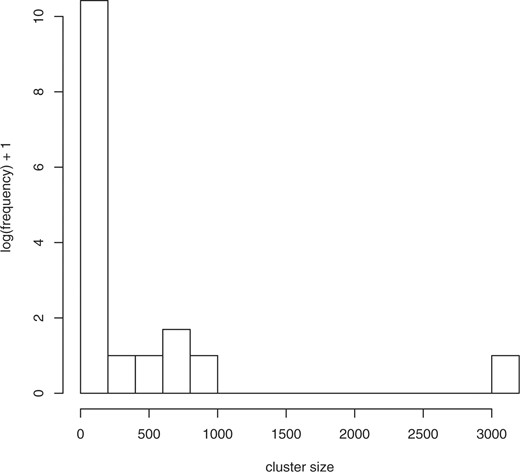

It is clear from comparing the 1yz counts, corresponding to the transformations including abstraction (the columns in the right section of Table 1), to the 0yz counts without abstraction (the columns in the left section of the Table 1), that the abstraction transformation has the most power in terms of clustering terms together, as it is able to reduce the number of clusters for the source terms by nearly half relative to not applying that transformation. No other transformation has such a dramatic effect—the individual compression effect of the other two transformations ranges from 0.4% to 1.2% in contrast to the 46% reduction from the number of 000 clusters to the number of 100 clusters. Intuitively, the abstraction transformation groups together semantically similar terms, and enables us to consider semantic ‘families’ of terms for univocality violations. Figures 1–3 show the (log) distribution of cluster sizes for xyz=000, 100 and 111. It can be seen that the number of large clusters increases dramatically with application of the abstraction transformation, and somewhat more when all transformations have been applied. In Table 2, we break down the abstraction type observed in the 1yz clusters. We see that fully half of these clusters have been created through one or both abstractions.

Breakdown of the 100 clusters by abstraction type

| Abstraction . | Count . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| CTERM only | 2489 | 20 |

| GTERM only | 3840 | 30 |

| Both CTERM and GTERM | 1415 | 11 |

| No abstraction | 4960 | 39 |

| Abstraction . | Count . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| CTERM only | 2489 | 20 |

| GTERM only | 3840 | 30 |

| Both CTERM and GTERM | 1415 | 11 |

| No abstraction | 4960 | 39 |

Breakdown of the 100 clusters by abstraction type

| Abstraction . | Count . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| CTERM only | 2489 | 20 |

| GTERM only | 3840 | 30 |

| Both CTERM and GTERM | 1415 | 11 |

| No abstraction | 4960 | 39 |

| Abstraction . | Count . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| CTERM only | 2489 | 20 |

| GTERM only | 3840 | 30 |

| Both CTERM and GTERM | 1415 | 11 |

| No abstraction | 4960 | 39 |

Among the 100 clusters, we find a cluster capturing a common form in the GO: 100 {regulat of GTERM}. This cluster has 803 members, and an excerpt of those terms appears in Example 4 to give a sense of the effect of the abstraction transformation. It can be seen that the basic structure of each term is similar, while there is still substantial variation among them.

Example 4.

100 {regulat of GTERM}

GO:0051270 – regulation of cell motility

GO:0030449 – regulation of complement activation

GO:0010058 – regulation of atrichoblast fate specification

GO:0045387 – regulation of interleukin-20 biosynthetic process

GO:0045652 – regulation of megakaryocyte differentiation

GO:0045655 – regulation of monocyte differentiation

GO:0050812 – regulation of acyl-CoA biosynthetic process

GO:0050818 – regulation of coagulation

GO:0002923 – regulation of humoral immune response mediated by circulating immunoglobulin

GO:0002920 – regulation of humoral immune response

GO:0043416 – regulation of skeletal muscle regeneration

…

As shown in Table 3, the application of the automated heuristic search to the clusters identified 237 xyz=101, 110 or 111 clusters that potentially contain non-univocal terms. Of these, 47 were redundant—e.g. the 111 transformation contained the identical set of terms to the corresponding 101 transformation. The second occurrence of a cluster of terms was identified automatically and discarded in the analysis. This left 190 clusters to be manually reviewed by the first author. Of these clusters, 67 (35%), were identified as containing one or more terms that were not univocal with other terms in the cluster. This number of true positive clusters represents only 0.03% of the source GO terms. The total number of terms in these 67 clusters is 374. Many of the terms in each cluster are in the ‘correct’ (standard) form, while at least one would be in the non-univocal form. We did not specifically count the number of terms that were not univocal, as the decision as to which form is standard and which is non-univocal is a curation decision for the ontology curators.

Results of heuristic search for univocality violations

| . | No. of clusters . | Proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Total candidates | 237 | |

| Identical | 47 | |

| False positive | 123 | 65 |

| True positive | 67 | 35 |

| . | No. of clusters . | Proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Total candidates | 237 | |

| Identical | 47 | |

| False positive | 123 | 65 |

| True positive | 67 | 35 |

Results of heuristic search for univocality violations

| . | No. of clusters . | Proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Total candidates | 237 | |

| Identical | 47 | |

| False positive | 123 | 65 |

| True positive | 67 | 35 |

| . | No. of clusters . | Proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Total candidates | 237 | |

| Identical | 47 | |

| False positive | 123 | 65 |

| True positive | 67 | 35 |

It is important to note that this small number of univocality failures actually indicates that in general, the GO is quite univocal, and that overall the quality of its terms is therefore high. It also gives an indication of how difficult in practice it is to find univocality violations in the GO, and further motivates the need for computational tools to generate non-univocal term candidates. As lexical resources become increasingly larger, it becomes correspondingly more difficult to locate errors in them. Finding problems in a very errorful resource is easy; finding them in a mostly correct resource is an entirely different challenge. It would be impossible to manually check all 25K terms in the GO, let alone pairwise combinations, for consistency. Looking through 190 clusters is feasible and was done in approximately 12 person hours without a specialized interface to the data.

4.1 Analysis of true positives

Analysis of the identified univocality violations reveals certain patterns of differences in expression. The most frequent source of failure of univocality is syntactic alternations of nominalization structures. It was previously observed by Cohen et al. (2008) that alternations are common in biomedical text, and in particular alternations of verb nominalizations, and we see the same phenomenon in the terms of the GO. Out of the 67 clusters with univocality failures we identified, 30 (45%) were a result of differences where one term contained a phrase of the form ‘X Y’, while another term contained a semantically comparable variant phrase ‘Y of X’ or ‘Y in X’. We see examples of these violations in Examples 5 and 6. Terms GO:0052350 and GO:0052351 should be rephrased as ‘induction by organism of symbiont induced systemic resistance’ and ‘induction by organism of symbiont systemic acquired resistance’, respectively, for parallelism. An additional 11 cases (16%) can be attributed to more specific alternations, as in Example 7. These cases rely on both the stopword and reordering transformations in order to recognize the difference in phrasing.

Example 5.

111 {GTERM GTERM organis symbion}

GO:0052387 – induction by organism ofsymbiontapoptosis

GO:0052351 – induction by organism of systemic acquired resistancein symbiont

GO:0052350 – induction by organism of induced systemic resistancein symbiont

GO:0052560 – induction by organism ofsymbiontimmune response

GO:0052399 – induction by organism ofsymbiontprogrammed cell death

GO:0052396 – induction by organism ofsymbiontnon-apoptotic programmed cell death

Example 6.

111 {GTERM ventric zone}

GO:0021804 – negative regulation of cell adhesionin the ventricular zone

GO:0021847 – neuroblast divisionin the ventricular zone

GO:0021900 – ventricular zonecell fate commitment

Example 7.

111 {GTERM selecti site}

GO:0000282 – cellular budsite selection

GO:0000918 – selection of sitefor barrier septum formation

A few (4) additional cases of univocality violations resulting from alternations turn out to be true positives from the perspective of this study, but yet the existing phrasing is in line with GO conventions. Modifying these to be perfectly univocal would introduce other irregularities in the term structure. See, for instance, Example 8. Term GO:0003100, ‘regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure by endothelin’, could be rephrased as ‘endothelin regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure’. However, given that the predominant convention in the GO is to employ the structure regulation of GTERM for regulation processes (see also Example 4), modifying this term for univocality would violate a broader convention in use in the GO and as such this change is not advisable.

Example 8.

111 {GTERM endothe} (partial listing)

GO:0003100 – regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure byendothelin

GO:0004962 – endothelinreceptor activity

The second most common variation, occurring 17 times, sometimes at the same time as an alternation, is to use a determiner (‘the’, ‘a(n)’) in front of a noun in one term, while it is left out of a comparable term. These are cases in which the stopword removal is the critical transformation for recognizing the univocality violation. We see two such cases in Examples 9 and 10. For term GO:0001759 in Example 10, the corrected form for univocality should be ‘organ induction’.

Example 9.

110 {GTERM forebra}

GO:0021861 – radial glial cell differentiation inthe forebrain

GO:0021846 – cell proliferation inforebrain

GO:0021872 – generation of neurons inthe forebrain

Example 10.

111 {GTERM organ}

GO:0031100 – organregeneration

GO:0035265 – organgrowth

GO:0010260 – organsenescence

GO:0001759 – induction ofan organ

A few true positives reflect a univocality failure due to inconsistent use of punctuation in combination with prepositions. We found non-univocal pairs as shown in Examples 11–14. Example 14 is one of the trickiest univocality failures we discovered. Our suggestion is that GO:0042770 should be rephrased as ‘signal transduction in response to DNA damage’ to be univocal with GO:0043247.

Example 11.

GO:0030614 – oxidoreductase activity, acting on phosphorus or arsenic in donors, with disulfide as acceptor

GO:0016624 – oxidoreductase activity, acting on the aldehyde or oxo group of donors, disulfide as acceptor

Example 12.

GO:0016647 – oxidoreductase activity, acting on the CH-NH group of donors, oxygen as acceptor

GO:0046997 – oxidoreductase activity, acting on the CH-NH group of donors, with a flavin as acceptor

Example 13.

GO:0016653 – oxidoreductase activity, acting on NADH or NADPH, heme protein as acceptor

GO:0016658 – oxidoreductase activity, acting on NADH or NADPH, flavin as acceptor

GO:0050664 – oxidoreductase activity, acting on NADH or NADPH, with oxygen as acceptor

Example 14.

GO:0043247 – telomere maintenancein response to DNA damage

GO:0042770 – DNA damage response, signal transduction

The remaining true positives are a grab bag of small errors, some reflecting variations in word choices (e.g. ‘within’ versus ‘in’ and ‘substrate-specific’ verus ‘substrate-dependent’), or the inclusion of superfluous words like ‘other’ (GO:0016764, ‘transferase activity, transferring other glycosyl groups’ versus GO:0016757, ‘transferase activity, transferring glycosyl groups’), which may have some significance in the broader context of the GO. In general, these could be straightforwardly rectified.

4.2 Analysis of false positives

In manual review of the 190 clusters, we counted the clusters that did not actually represent cases of univocality violations (the false positives). We also categorized the reason that the terms in the cluster are in fact univocal despite their collapse together as a result of our transformations. Note that several reasons were given in some cases. The breakdown appears in Table 4.

Breakdown of false positives

| . | No. of clusters . | False positives proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Semantic import of stopword | 61 | 50 |

| Non-parallel structure | 33 | 27 |

| Semantic import of stemming | 21 | 17 |

| Syntactic variation | 6 | 5 |

| Semantic import of word order | 1 | 1 |

| Misclassified content word | 1 | 1 |

| . | No. of clusters . | False positives proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Semantic import of stopword | 61 | 50 |

| Non-parallel structure | 33 | 27 |

| Semantic import of stemming | 21 | 17 |

| Syntactic variation | 6 | 5 |

| Semantic import of word order | 1 | 1 |

| Misclassified content word | 1 | 1 |

Breakdown of false positives

| . | No. of clusters . | False positives proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Semantic import of stopword | 61 | 50 |

| Non-parallel structure | 33 | 27 |

| Semantic import of stemming | 21 | 17 |

| Syntactic variation | 6 | 5 |

| Semantic import of word order | 1 | 1 |

| Misclassified content word | 1 | 1 |

| . | No. of clusters . | False positives proportion (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Semantic import of stopword | 61 | 50 |

| Non-parallel structure | 33 | 27 |

| Semantic import of stemming | 21 | 17 |

| Syntactic variation | 6 | 5 |

| Semantic import of word order | 1 | 1 |

| Misclassified content word | 1 | 1 |

The primary source of false positives in our analysis, labeled semantic import of stopword in the table, is that when stopwords are removed, we may remove words that are in fact indicating important semantic relationships. Consider the minimal pair shown in Example 15. In this case, removing the stopwords and reordering the constituent tokens clusters these two terms together, while in fact semantically they express an opposite relationship: in the first term, the host is acting on the symbiont, and in the second, the symbiont is acting on the host. In general, the stopwords specify either the role of one of the entities, or the location of a process, and the choice of stopword is significant. In Example 16, the choice of ‘at’ versus ‘in’ depends on the specific relationship between the process and its location. Similarly, Example 17 shows how the word choice can depend on the type of entities being related through a stopword—‘in’ is appropriate for a location, while ‘during’ is appropriate for an event (Zelinsky-Wibbelt, 1993).

Example 15.

111 {CTERM GTERM levels modulat symbion} (partial listing)

GO:0052430 – modulationby host of symbiontRNA levels

GO:0052018 – modulationby symbiont of hostRNA levels

Example 16.

110 {CTERM CTERM galacto GTERM}

GO:0033580 – protein amino acid galactosylationatcell surface

GO:0033582 – protein amino acid galactosylationincytosol

GO:0033579 – protein amino acid galactosylationinendoplasmic reticulum

Example 17.

110 {callose deposit GTERM}

GO:0052542 – callose depositionduringdefense response

GO:0052543 – callose depositionincell wall

The false positives categorized as non-parallel structure correspond to clusters in which the member terms do not have an obvious common structure on which to evaluate univocality. Essentially, these are clusters in which the transformations have caused terms to look alike which really are not. These are generally clusters that are characterized by sequences of GTERM and/or CTERM tokens and no other content-bearing tokens. Several examples appear in Examples 18–20.

Example 18.

110 {CTERM CTERM}

GO:0005204 – chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan

GO:0006088 – acetate to acetyl-CoA

GO:0015641 – lipoprotein toxin

Example 19.

110 {GTERM GTERM GTERM} (partial listing)

GO:0019896 – axon transport of mitochondrion

GO:0047496 – vesicle transport along microtubule

GO:0047497 – mitochondrion transport along microtubule

GO:0060146 – host gene silencing in virus induced gene silencing

GO:0032066 – nucleolus to nucleoplasm transport

GO:0052067 – negative regulation by symbiont of entry into host cell via phagocytosis

Example 20.

111 {GTERM storage}

GO:0001506 – neurotransmitter biosynthetic process and storage GO:0000322 – storage vacuole

In their ontology alignment work, Johnson et al. (2006) found that while stemming does increase the number of proposed alignments among two ontologies, this comes at a cost of low correctness. Here, we find a similar phenomenon in that stemming may incorrectly conflate multiple terms. Particularly problematic is the conflation of word variants that express a semantic role difference. Considering a slight transformation of the cluster in Example 4, we identify the following members of that cluster:

Example 21.

110 {regulat GTERM} (partial listing)

GO:0045066 – regulatoryT cell differentiation

GO:0045069 – regulationof viral genome replication

GO:0045055 – regulatedsecretory pathway

GO:0031347 – regulationof defense response

Stemming results in the conflation of ‘regulation’, ‘regulated’, and ‘regulatory’ to the common stem ‘regulat’. However, each of these word forms expresses a somewhat different relationship that is lost when they are reduced to a common representation and as a result we have a false positive cluster. Another similar problematic example is found in Example 22. We also identified one case (mis-classified content word) in which a content word was treated as a stopword by our algorithm and erroneously removed (GO:0006328 ‘AT binding’ was reduced to 110{GTERM}).

Example 22.

110 {activat GTERM}

GO:0001905 – activationof membrane attack complex

GO:0002253 – activationof immune response

GO:0050798 – activatedT cell proliferation

GO:0051522 – activationof monopolar cell growth

GO:0051519 – activationof bipolar cell growth

GO:0002218 – activationof innate immune response

GO:0032397 – activatingMHC class I receptor activity

The false positive category syntactic variation is similar to the non-parallel structure but refers more specifically to terms which are mostly parallel but show some semantically relevant syntactic variation in expression. One example is in Example 23. This variation uses coordination to link two related concepts together.

Example 23.

110 {GTERM mainten}

GO:0032360 – provirus maintenance

GO:0045216 – intercellular junctionassembly and maintenance

GO:0045217 – intercellular junctionmaintenance

GO:0045218 – zonula adherens maintenance

The final false positive category semantic import of word order was assigned in one case where the reordering transformation introduces the appearance of non-univocality where in fact there was none. For this case, the cluster shown in 24 merged with 25 at the 111 level. As a result, the implication is that one of these clusters should be rephrased to parallel the structure of the other cluster, for instance by rephrasing ‘apoptosis inhibitor activity’ to be ‘inhibitor apoptosis activity’ or, taking the other cluster as the primary case, rephrasing ‘gibberellin binding activity’ to be ‘binding gibberellin activity’. Either of these transformations would result in a change in the overall meaning of the term and would be incorrect.

Example 24.

110 {GTERM CTERM activit}

GO:0005194 – cell adhesion molecule activity

GO:0003712 – transcription cofactor activity

GO:0008189 – apoptosis inhibitor activity

GO:0003794 – acute-phase response protein activity

GO:0000772 – mating pheromone activity

Example 25.

110 {CTERM GTERM activit}

GO:0045306 – inhibitor of the establishment of competence for transformation activity

GO:0010331 – gibberellin binding activity

GO:0010427 – abscisic acid binding activity

5 DISCUSSION

Though our automated method was able to identify many good examples of univocality violations that upon correction will contribute to improved quality of the GO, it required substantial manual effort to separate the true positives from the false positives. The analysis of both sets of results shows that it is important to distinguish purely syntactic transformations of a term—transformations which do not impact the meaning conveyed by that term—from transformations which have semantic import. The transformations we experimented with here were effective in grouping semantically similar terms together, as evidenced by the cluster data presented above in Table 1, but they were overly aggressive and as such also grouped together terms with important semantic differences. This led to the inclusion of many false positive cases among the identified potential cases.

It appears on the basis of these experiments that identification of univocality violations would be best achieved by specifically searching for syntactic alternations that are known to preserve the meaning of the terms, in addition to punctuation variations. An alternative, but related, idea is to filter the output of the current algorithms to remove those clusters which seem to vary only according to a known alternation with semantic import. This would allow some of the more unpredictable ‘grab bag’ true positives to persist into the set evaluated manually while eliminating many of the false positives that stem from the semantic import of stopwords.

There are also, of course, potentially other violations of univocality in the GO that we have not identified in this analysis. These may be identifiable through a more specific treatment of alternations as suggested above. The analysis did also suggest several additional avenues for variations that we could specifically look for, including use of determiners and words like ‘other’, but also taking more advantage of abstraction by converting the tokens affecting naming variation—integers, Greek letters and individual letters—to a generic token such as NUMBER. We could further take advantage of abstraction by incorporating ontologies such as the Cell Ontology (CL) in addition to ChEBI, or by generalizing over linguistic forms, such as abstracting words like ‘regulation’ and ‘proliferation’ to -ION_WORD. The latter especially may provide access to some even less obvious univocality violations. Similarly, we may find that we have fewer non-parallel structure false positive cases if we take advantage of the structure of the GO and abstract the biological process, molecular function and cellular component terms separately, analogously to what is done in Bada and Hunter (2008).

Univocality violations that derive from singular/plural variation would in our current approach be placed into the same cluster during preprocessing and would not be picked up by our heuristic search. These could be automatically identified through a more sophisticated treatment of stemming, in which we track suffixes and compare the morphological structure of comparable terms. Finally, we are likely missing univocality violations due to our maintenance of redundancy in the cluster representations (see Section 3). We plan to add a fourth transformation which reintroduces redundancy removal, and explore a refinement to our heuristic search which makes effective use of that additional level of cluster merging.

Ultimately, we would like to have a set of tools that identifies univocality violations with a high rate of accuracy and less manual intervention. This could then be used to establish a quality metric for ontologies or ontology versions based on the proportion of terms in an ontology that are not univocal. However, even the tools as they stand today provide significant utility—reducing the number of terms that need to be assessed manually from over 25 000 to under 200, with a reasonably good true positive rate. Through the application of our methodology, we have made detection of univocality violations across a large ontology feasible. To the extent that we can improve the transformation and clustering or the heuristic search steps in future work, we can further reduce the set of terms to be assessed manually, and/or improve the true positive rate within that set.

6 CONCLUSION

We have introduced an automated method for identifying violations of univocality among a set of controlled vocabulary terms that reduces the set of terms that need to be examined manually to a manageable size. Using the method, we were able to identify 67 examples of univocality violations in the GO that can be addressed in order to improve the quality of that ontology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the GO consortium for alerting us to the need for an investigation of the issue explored in this article, and David Hill for introducing the term univocality in this context at the OBO Quality Assurance workshop in January 2008. We also thank Helen Johnson for her input to discussions at the start of this work and Mike Bada for reviewing the semantics of a few clusters and giving feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (5R01 GM083649-02 to K.V., K.B.C. and L.H.); National Institutes of Health training (5T15 LM009451-02 to D.D.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

1In computer science, a heuristic search is an algorithm that ignores whether the solution to the problem can be proven to be correct, but which usually produces a good solution. Here, we are not certain whether our algorithm will find all occurrences of univocality violations that exist in the transformation clusters, but we know that it will find many cases. There are other potential heuristics for this search that could be experimented with and we plan to do so in future work.